Dear Drink To That Reader,

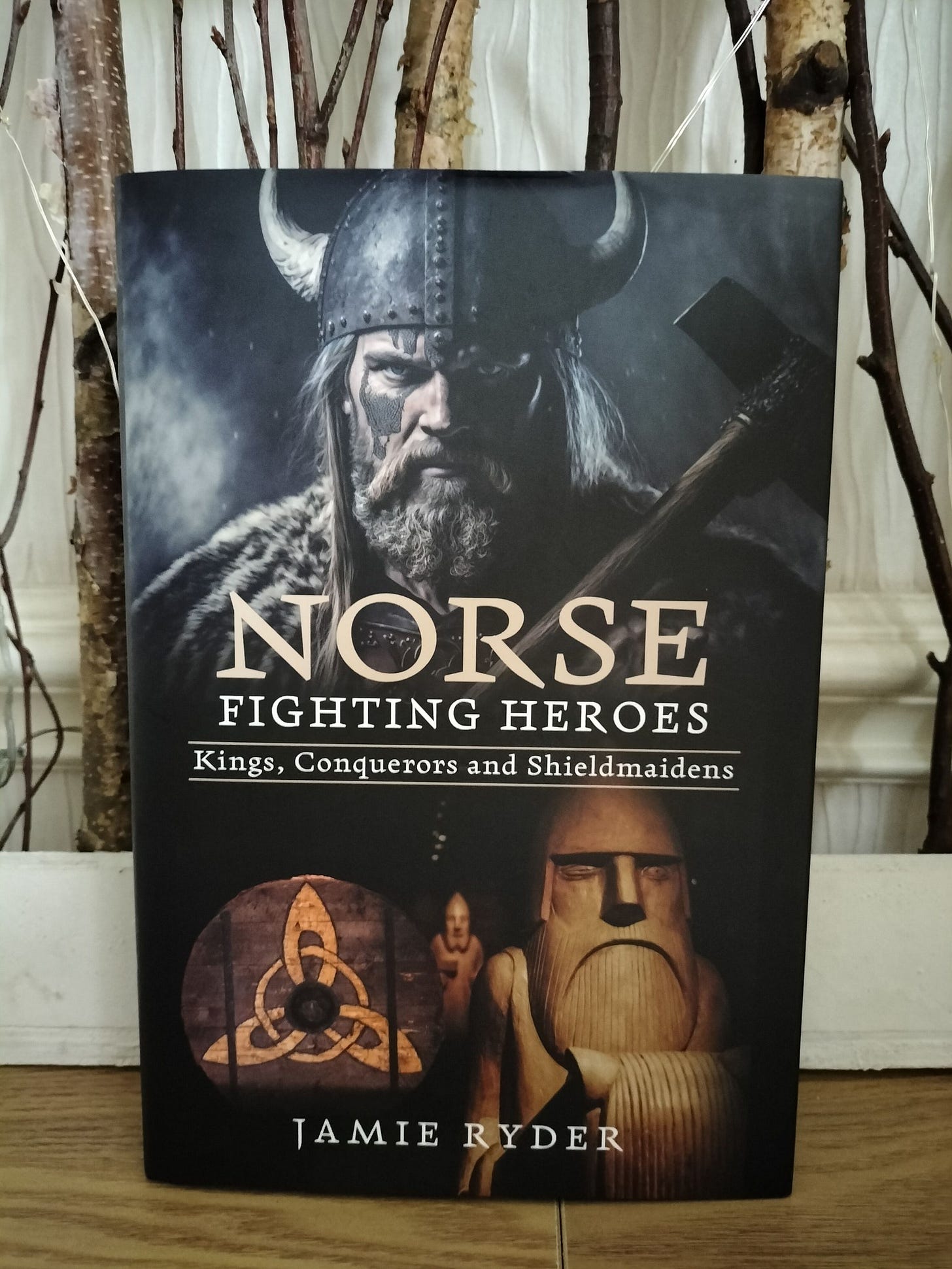

This week’s Sip Of Wisdom comes from my book Norse Fighting Heroes: Kings, Conquerors & Shield Maidens.

The day was hot and humid. Two armies glared at each other from across the field. On one side, the hard-bitten warriors of Ragnar Lodbrok, king of Denmark; on the other, the implacable war-wolves of Sorle, ruler of the Swedes. The Danish king, having wanted to avoid a bloodbath, agreed to a duel between a small band from both sides. Accompanying him were his three sons Fridleif, Radbard and Bjorn.

Bjorn stayed close to his siblings and father, watching the expressions on their faces. He turned his head to study their foes. Sorle had chosen the champion Starkad and Starkard had chosen his seven sons to fight at his side.

The prospect of fighting against a larger force got Bjorn’s blood up and he looked back to his father and brothers for a final time, recognising the battle-speak between them. Enough words had been spent. To Bjorn, only one thing mattered: to protect his family at any cost and prove himself worthy of Ragnar.

As he raised his axe, Bjorn felt something in the air. Perhaps it was the valkyries screaming past him. Perhaps it was the disir, the female spirits that watched over his clan and guided each swing and strike that he made.

Whatever it was, Bjorn lost himself to the rhythm and flow of battle until he was left standing with his father and brothers, Starkad and his sons lying dead at their feet. With the fighting frenzy slipping away, Bjorn became conscious of injury. He checked his armour and body. He remained unbloodied, unpierced, unbroken. So impressed was Ragnar with his son’s bravery that he left Sweden in his hands to govern.

From that day forward Bjorn would also carry a new name, a name that spoke of his strength and imperviousness: Bjorn Ironside.

The life of Bjorn Ironside is as legendary as those of his father Ragnar and brother Ivar the Boneless. It’s also an interesting case study for looking at Viking raids in the Mediterranean.

Raiding in new waters

While the exact date of the first raid of the Iberian Peninsula and Al- Andalus (Muslim Spain) is hard to determine, some ideas can be seen in the story of Don Teudo Rico and his defeat of the Norsemen in 842. According to the story, the Norse first landed in the fishing port of Luarca, close to the city of Gijon. Don Rico and his soldiers drove them off and killed a Norse chieftain with his mace. A plaque was even created to commemorate the victory.

In Arabic texts, there’s a strong indication of the fear these Northern raiders inspired. According to the historian Ibn Idhari, who may have been referring to a similar stretch of time when the Norse moved on to Al-Andalus, they ‘arrived in about 80 ships. One might say they had, as it were, filled the ocean with dark red birds, in the same way as they had filled the hearts of men with fear and trembling. After landing at Lisbon, they sailed to Cadiz, then to Sidonia, then to Seville. They besieged this city and took it by storm.’

So, while Bjorn Ironside wasn’t the first Norseman to reach the Mediterranean and even though his expeditions are filled with fantastic elements befitting a legendary saga, the stories of his raids show the ingenuity and tenacity of the Scandinavians who journeyed south.

In the 850s, Bjorn set out to raid Francia with either his brother Hvitserk or another accomplished leader called Hastein and kept going along the Frankish coast, voyaging beyond the waters that Ragnar Lodbrok had raided.

An early attack on the city of Santiago de Compostela didn’t go to plan for Bjorn and his co-captain, but it didn’t deter them from moving forward. At some point, the raiders came into conflict with Muhammad I, the Emir of Cordoba, whose forces burned longships with the perennial repeller of Norse ferocity and grit: Greek Fire. Bjorn made the decision to try his luck elsewhere and pushed further south, passing through the Gibraltar Straits. In these warm, Mediterranean waters, Bjorn finally found success, being responsible for plundering some of the cities that Ibn Idhari mentioned in his damning prose.

Bjorn’s next target was the coast of North Africa, where he led raids against the Emirate of Nikor, going so far as to hold it for a week. The Norse took Moorish slaves, whom they called blamenn and sold on in Irish slave markets.

The man named Ironside carried on plundering into the south of Francia in the area that would become the French Riviera and settling down into a strategic position for the winter. In the spring, Bjorn guided his ships deep up the River Rhône, sacking as he went. But on reaching the city of Valence, they were pushed back.

Changing course again, Bjorn directed his battle-tested warriors towards Italy and into the shadow of a city that had birthed one of history’s greatest empires. Bjorn caught wind that he was near Rome and wanted to plunder the Holy City. In one of the most famous legendary examples of Viking guile, messages were sent to Rome to inform the clergy that the Norse leader had died. But his last wishes had been to convert to Christianity, and he wanted to be buried on holy ground.

The Christian leaders swallowed the lie and opened the gates to let in a coffin carried by a small gathering of Norse pallbearers. On reaching the main cathedral, Ironside (or Hastein depending on the sources) pounced from his coffin and he and his men revealed their weapons.

They cut through the crowd and flung open the gates so the Norse horde could rush into the city. Bjorn believed he made Rome submit to his will. Only later did he discover that the actual place he’d plundered was the town of Luna. Still, he revelled in his success. Moving on to Pisa, Ironside took more plunder and decided to circle back to the Straits of Gibraltar. It was finally time to go home.

Securing a legacy

Bjorn Ironside carved his name across the Mediterranean, though his violence and ambition had put a target on his back. Muhammad I and his fleet were waiting for him in the Gibraltar Straits and blocked his path. Like the blaze of some dragon from a Norse tale, fire rained down on Bjorn’s ships until only a third of his ships remained.

He and his most loyal followers were still able to escape and as they headed towards the Loire River and back home, Bjorn and Hastein couldn’t resist leading one final raid. So, they turned their attention towards Navarre and attacked the city of Pamplona, where they captured King Garcia and ransomed him back to his people for a large sum of money.

After this final score, sources differ on the fate of Bjorn Ironside. One theory is that he never made it home, that he was shipwrecked in Frisia and died losing everything. A more optimistic theory is he was able to avenge the death of his father Ragnar with his brothers in England and returned to Sweden, heavy with riches and stories.

In this version of his lifepath, Bjorn went on to found the Munso Dynasty of Sweden. In time, this great house would also become the ruling family of Denmark with generations of brave kings and explorers following the trail blazed by their legendary forebear. Bjorn was buried on the island of Munso, beneath a mound marked by a potent runestone. As to whether this is his true gravesite, there is little evidence to back up the claim, though valuable grave goods have been found in the area surrounding the mound, indicating the presence of a wealthy and respected Norse warrior.

In Bjorn Ironside, we see the wanderlust of the Norse personified and there is something timeless we can take away from this attitude to life. Travelling to new places and expanding our horizons is a healthy and worthwhile exercise, both physically and mentally.

Expanding the shores of our knowledge and voyaging through mental planes helps us grow, just as it can erode our sense of self if we go too far the wrong way. Travelling can be a means of escape, but it should never be to escape ourselves. For to find a fixed position within ourselves, a place to come back to means we’ll carry our homes with us wherever we go.

And as J. R. R. Tolkien, an admirer of Norse mythology and who found his own inspiration in the sagas, wrote so eloquently, ‘All that is gold does not glitter, Not all those who wander are lost; The old that is strong does not wither, deep roots are not reached by the frost.’